The Waltz of the Clocks

At the beginning of the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, author Gabriel García Márquez spends several pages describing the strange illness afflicting his characters and their fellow villagers: the plague of forgetfulness. One day, the main character realizes that he no longer needs to sleep and does not suffer from the harmful effects of sleep deprivation. He realizes that this

phenomenon is spreading among all the people in the village, like any contagious disease. Little by little, everyone fills their days and nights without worrying about

rest, but they all realize that the undesirable effect of this phenomenon is that their memory is slipping away. They forget the names of objects, their neighbors, and their family members. A whole part of their past is slipping away from them, and their reality is turning into a sterile confinement where the slightest action and its consequences

fade away. Our main character tries to find ways to combat amnesia. For example, he puts labels and signs with the supposed names

of things on each of them. But sometimes the names are not correct because they have already been forgotten. One day, someone arrives with a treatment,

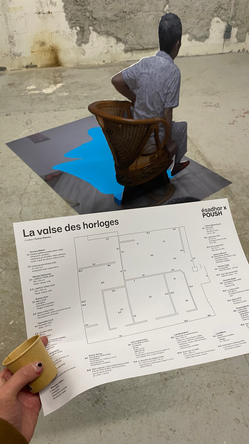

but we will stop there in this story. As in Márquez's story, where time and memory waver, 17 young artists who recently graduated from the École Supérieure d'Art et de Design Le Havre-Rouen (ESADHaR) explore these temporal oscillations and the traces they leave behind in the exhibition La valse des horloges (The Waltz of Clocks). They address the dissolution of individual and collective memory, the need to remember, to understand one's origins and to put them into perspective

with the signs of the times that intersect, mix and sometimes repel each other. The three-beat waltz - past, present, future - carries them away in a great rush, leaving traces and vestiges for us to discern.

In the basements of Poush, a place marked by traces of its past, the artists' practices meet within concrete walls.

This material is the backdrop for Zoé Lauberteaux's practice, which explores wastelands, those ruined areas that carry a past that is crumbling but not passing away. In

Emmanuelle Queinnec's paintings, fragile memories are not embodied in places, but in a mental space plagued by flashes of memory and narrative distortions.

Mariam Beltoueva also weaves together memory and fragments of the past. With her knights, of whom only their molted skins remain, we understand that the spectacular violence of history is

latent, and that it only takes a breath to rekindle the flames.

Further on, memory becomes a tool for struggle and transmission. Alexiane Trapp considers language to be essential to the ongoing struggle of feminist activist groups, and

Fatima-Marwa Zouzal reminds us of the constant pressure that state authority and patriarchy impose on racialized people and women. Feminist songs for one,

and the lullaby of a music box for the other, resonate throughout the exhibition space.

This collective strategy is also very important to Garance Wernert, who advocates a common approach to knowledge through the exploration of free software, often the fruit of collaborative intelligence. Her workshops become places where militant and popular discourse emerges, a theme continued by Lola Millard who, not without irony, combats classism, sexism, and their divisive effects. By playing with stereotypes of precariousness and hyperfemininity, sometimes considered vulgar, she draws attention to the logic of exclusion that underlies social relations.

It is in a more intimate dimension that this same notion of hyperfemininity fascinates Youssra Akkari. Taking up its codes, the artist recalls the periods in the lives of girls and

young women when their bodies are constrained by society's expectations. She then slightly shifts reality to play with normativity, as Lorène Genoyan

also strives to do. By diverting items with very specific uses, she invites us to shift slightly away from reality and blurs their context of use.

This dazzling effect that delights the senses is also very present in the literary and poetic work of Emma Genty, who allows herself to drift with fascination through natural landscapes

that become spaces for her personal projection.

This attachment to reality and the possibility of its transpositions is also at the heart of Lauralie Naumann's practice, who, in her installations, proposes

strangely performative situations where objects merge with the way they are named.

We understand that they could contain bodies, but for now they are empty. Lola Macharbert, in her technological, dramatic, and romantic weavings, also explores the theme of absence. Here, it is that of an imaginary lover who recalls memories while remaining desperately silent. The bond that unites them is tenuous and seems to be gradually dissolving. But this introspective work, which sometimes forces us to look within ourselves, can also make us realize how far we have strayed from our deepest attachments. This is the case with

Ruizhe Chen, who bears witness to an increasingly distant familiarity with their culture of origin and those close to them, even if it means having to rebuild ties within a chosen family. It is this same experience of uprooting tinged with a silent violence that inhabits the work of Stanislav Falkov. Here, we can only be spectators of the metamorphosis imposed on people who, like him, have had to go into exile and watch helplessly as time takes its toll and the authorities act with madness.

Sometimes, the brutality of the present can drive some people to seek refuge. Charlotte Simon offers a painting filled with universal signs inviting calm. But refuge can also be a double-edged sword, as suggested by Corentin Delahaie-Antibe, who presents a luminous trilobite, both protective and threatening. It acts as a guardian of the exhibition, bathing the whole in its light. Finally, the last guardian of this group could be Raphaëlle Curci, who, capturing the micro-phenomena that transcend time and invite collective rest, will undoubtedly allow us to calm the waltz of the clocks.

Thomas MAESTRO

Ruizhe Chen works on issues of identity. He constantly questions what connects him to and distances him from his Chinese culture of origin. The artist has been living in France for several years, developing a practice based on profound existential questions, the expression of his feelings, and the exploration of his memory. He has occasionally returned to China to visit his family, which has led him to question the notion of whether it is our biological family that connects us to our deepest origins, or whether other connections can be forged through a family of friends. Can intimacy be transposed to an uprooted context? This is what he expresses with his Maison Rose, a small building with no doors or windows. We can only circle around this home that keeps us at a distance, fantasizing about its contents, well protected between blind walls. One day, the artist placed this house in the middle of a field he could see from the window of the bus taking him to school. He then invited his classmates and

teachers to join him there, so that together they could get as close as possible to the impenetrable building. Locked away, inaccessible, and disappearing memories are also at the heart of his photographic sculptures Mami. Here we encounter, on a human scale, Ruizhe Chen's grandmother, who suffers from Alzheimer's disease. These silhouettes freeze a presence that is fading away, an identity that is dissolving along with her memories.

Thomas MAESTRO